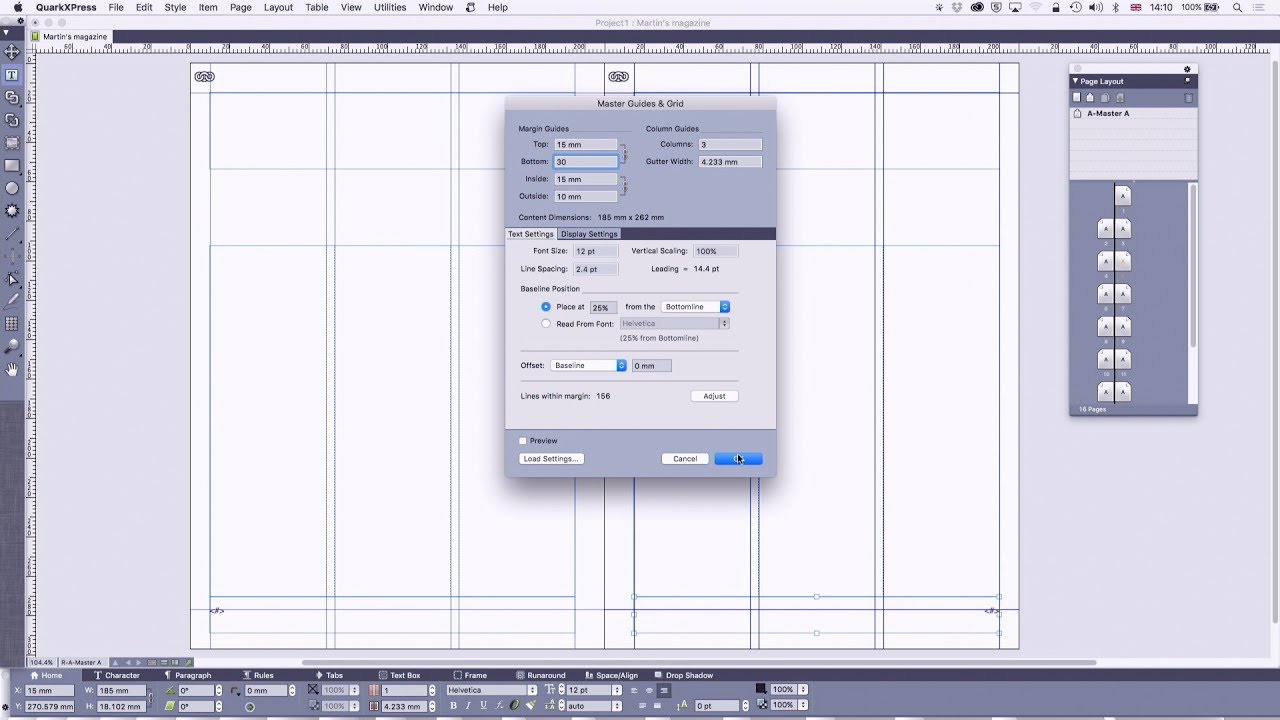

In such an interaction, the energy of the gluon would be converted into internal energy of a bottom quark which would then appear as a very heavy particle, called an excited bottom quark. A quark could instead be excited by the absorption of a gluon, as these are abundant in the proton collisions made by the LHC. However, it may be possible to “excite” the bottom quark in a way similar to an electron being excited to a higher orbit in an atom by the absorption of a photon. If a quark is made up of other constituent particles, the energy required to split them would be higher than the energies provided by the LHC. One such search performed by CMS physicists looks for an excited bottom quark. But if there is any lesson to be learned from the history above, it is that there is no reason to declare that we have reached the most fundamental of pieces to our universe! Thus, physicists at CMS continue to probe the existence of a substructure to the so-called “fundamental particles.” The electron remains, as far as we know, indivisible and is considered a “fundamental” particle along with the quarks, bosons, and other leptons, that make up the Standard Model of particle physics. With other quark combination, even other hadrons are possible! Just as different combinations of protons, neutrons, and electrons can create different atoms, different quark combinations can construct the proton and neutron. In the latter half of the 20 th century, we learned that even the proton and neutron are divisible into quarks and gluons. So much for “uncuttable”!įigure 1: All known atoms can be made of electrons and quarks (credit: CERN)Īs we know today, two smaller parts make up the nucleus inside atoms – the proton and the neutron - and combinations of these two particles with electrons can create any atom. Thompson’s discovery of the first subatomic particle – the electron – and Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden’s observation of the nucleus showed that the atom was also composed of parts, leading to the development of the Bohr model. After sorting materials based on experimental observations, scientists developed a theory that a common piece connects the elements and, borrowing from Democritus’ approach, they called it the atom. Atomism describes the world as being made of an infinite number of indivisible particles. The Greek philosopher Democritus proposed the theory of atomism (from the Greek atomos, meaning “uncuttable”). Since ancient times, philosophers and physicists alike have discussed the prospect that all pieces of the observable universe are made up of one or more “indivisible” particles.

A new result by the CMS collaboration examines the data collected between 20 for evidence that quarks are composite particles and not elementary.

Physicists continue to question if the particles we know of are the most fundamental.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)